Filmi Women II: Waheeda Rehman in Reshma aur Shera (1971) and Pyaasa (1957)

|

| Rakhee as the widowed bride in Reshma aur Shera |

As with my first filmi women post, here I am primarily concerned with whether or not the typical "suffering heroine" of Hindi film can ever actually be a liberated figure. Again, I'm not exactly expecting a feminist ideal, but rather a presentation of something to aspire to--rather than to run away from. I'm seeking someone to admire, rather than pity. I'm waiting for that character I would introduce to my hypothetical daughter someday, with the admonition, "Look at her. She is something, isn't she? Don't you wonder if you would be that strong, that fierce, that courageous in the same circumstances?"

Kick-ass female characters are by far the most visible icons of female liberation. It's much more difficult (and worth taking time to analyze via this blog) to point to female characters that suffer--yet manage to rise above traditional gender roles and grasp at a unique kind of female agency. Sure, Zeenat Aman's character in Don (1978) is fabulously subversive in her show of physical strength and daring. But something like Yash Chopra's Daag (1973) is more fun to deconstruct . . . precisely because of it's conflicting and complex depiction of women.

|

| The character of Geeta in Seeta aur Geeta is THE iconic "strong woman" in Hindi cinema. Yet, I prefer Hema's complex, yet still liberated, character in Raja Jani (1972) as a role model. |

But before moving forward, I must confess: I admit it took me a long while to warm up to Waheeda Rehman. (Gasp!)

I referenced her character in Namak Halaal (1982) as a prime example of everything I hate about the "suffering filmi heroine" in my last Filmi Women post. I felt her character's oppression was depicted point blank . . . without accompanying commentary or counterpoint. (Where are Salim-Javed when you need them?) To be fair, it wasn't just Namak Halaal contributing to my dislike. Frankly, in every one of the handful of late 70s, early 80s films I caught Waheeda in, I found her irritating, and I wasn't quite sure why. I SHOULD know by now, given my first reaction (ughhh) to my beloved Rakhee in an uninspired role, that I am more likely to react with violent dislike to a good actor in a bad role, than I am a bad actor in a good role. I hate watching passively, feeling near-physical pain at the talent and creative energy going to waste . . . and I hate having to clench my teeth and grip my chair (and think of England) in order to finish the film because of one bad apple of a performance.

|

| (Pyaasa, 1957.) Yes. Yes, I was, Johnny Walker. Please ask Waheeda-ji to forgive me. |

Similarly, her role in Ghungroo (1983), gives a platform to the force of her personality, but locks her in a dramatic prison of sorts--fashioned from her character's own outdated principles. Now I can see that these types of roles wouldn't do anyone any favors . . . and even the best actor can be defeated by them (much less women in the "real world," who find themselves stuck in rigid roles the world has outgrown).

|

| Ghungroo (1983). Let's face it, anyone making these two cuties miserable is someone you are probably going to dislike. |

Let's just say, as I dipped further back into Waheeda's career, I was in for a massive surprise. Apparently she hadn't ALWAYS stood for the dark side of the Bhartiya Nari. (Though I suppose it wouldn't have been her fault if she had.)

Now, whenever I hear the word "fierce," I will be hard-pressed to think of anyone else but the titular "Reshma" of the doomed pair of Reshma aur Shera . . . protecting her sworn enemy from a lynch mob, and telling the murderous villagers to get the hell out.

And when I picture the kind of selfless love I can get on board with, I will see Waheeda's shadowed, yet, glowing face in Pyaasa, as she gazes with desire on the poet she adores, unbeknownst to him:

FILM I

Waheeda in Pyaasa:

As much as interesting performances abound in Pyaasa . . . |

| I haven't seen any other performances yet by Guru Dutt, but he definitely won me over in this one. |

But was the suffering liberating?

Pyaasa humanizes "need" and "longing." Here, needs are just needs, no matter WHO is experiencing that need. This theme alone causes a leveling effect throughout the social strata and gender strata of the various characters. Over and over, every single character is shown to have needs, both material and spiritual.But since this is a highly moral tale, choosing which need to satisfy above all else divides the good characters from the bad. Those who recognize the needs of love and art first, despite their poverty, are ultimately shown to be the better souls. Furthermore, characters who might have otherwise been condemned by us because of their weaknesses, are instead purified and almost deified for their poetic (and often futile) feelings of love and longing. Unrequited longing is almost held up as the ultimate virtue. ("Pyaasa" means "Thirsty," after all.)

While I am used to seeing every color of romantic longing in Hindi cinema, I was not prepared for the unadorned longing in Pyaasa. I haven't yet put my finger on why this kind of hunger/thirst felt so damn unusual (for any film from any industry) . . . maybe you can tell me. All I can say is, I wonder if everyone on this film, male and female, decided to do an extended fast, a la Karva Chauth or something. It's almost the only way I can account for the raw need present in everyone's eyes at all times.

In this stunning sequence (and maybe the most memorable of the film), Guru Dutt's poet (Vijay) stands on the roof, listening to the sounds of a performance below. Gulabo follows behind him, staying in the shadows, watching him as the song below speaks for her lust and longing.

But her sliver of hope is short-lived. She realizes that her longing must go unfulfilled. She has no chances with him. She kisses the air behind his shoulder, and backs away, into the shadowy recesses of the slums.

Amazingly (to me at least) I think the barrier Waheeda's character feels here is that of the poet's fixation with his lost love . . . not the obvious: her "shameful" profession. He is so lost in thought that he doesn't react to her presence, or even to her near-embrace. He can only thirst for the one who played him false. Ironically, true love is right in front of him, or rather behind him, in this case. I think she sees very clearly, and painfully, that she is not in his heart yet, even though he is written all over hers.

Like a good socialist melodrama piece, Pyaasa also surgically removes the "shame" out of poverty and re-attaches it to daulat (wealth). (I couldn't help but compare Pyaasa to my favorite Chaplin message-y, soulful, and cheerfully socialist melodramas: Modern Times and City Lights. They're soooooo soooooo alike in their goodness--in a kindred-y spirit, let's get together and write a banned underground newspaper that's completely made up of poetry-kind of way.)

Furthermore, this is very much a story about economics, period: about the ethics of buying and selling. The film dares to ask, "At what point does one sell oneself, not just one's skills?" Prostitution is NOT portrayed as the worse kind of selling of oneself, or the worst kind of buying of flesh, for that matter.

After Vijay is wrongly presumed dead, Gulabo goes to his old girlfriend's (Meena, played with chilling calculation by Mala Sinha) husband to try to get his poems published. She quickly realizes she has stepped into the hot, grasping, unsolved mess of Vijay's old life.

Meena, who once gave Vijay up for the comforts of her loveless marriage, can't imagine that Gulabo wouldn't want money for the poems.

After, all, Gulabo sells her body. Why wouldn't she sell a few pieces of paper? But, of course, to Gulabo, selling Vijay's poems would be akin to selling his soul. Instead of asking for payment, she pays Meena's husband (with her entire savings no less) to publish the work posthumously.

The plot choices and internal dialogue that normally dehumanizes women in Hindi films, or even just stories in general (control or denial of their needs/judgment toward their social situation or profession or sexual history), these things are all steadfastly eliminated and de-legitimized in Pyaasa, one by one. Gulabo starts with a precious sense of self respect despite everything--and walks out of the film having gained a social legitimacy from the one and only person of whom she craves it.

Wonderfully, this film also treats the Vijay with an equal hand. He realizes that the one person who he wanted legitimacy from--cannot give him anything meaningful, ever. He finally sees the person who's love and respect actually means something . . . *Spoiler * Gulabo, of course. Reflecting this equality, both characters walk off into the sunset together (like Chaplin and Paulette Goddard in Modern Times). No longer do they need to sell themselves for survival or legitimacy's-sake. Neither will they be despised for what they don't have, nor will they be sold for what they do. Together they will throw off the world and decide to love in idealistic anonymity. Seems like liberation to me.

FILM II

Now, for Reshma aur Shera . . .

I'm not going to attempt to compete with other excellent synopses of this film, so you can find full reviews, analysis, and more screen-caps here, and here.To a Western viewer, RaS reads like a variant on Romeo and Juliet--yet the story grows and builds into a very different tree than one might expect--perhaps because of it's roots in the gritty, and surprisingly realistically depicted soil of Rajasthan. Despite its anthropologically literate face, this is a prescriptive, rather than a descriptive film. RaS goes to great lengths to condemn and absurdify the perpetuation of all cultures of violence, and proposes that women can play a key role in ending the cycle of bloodshed.

To me, however, the journey of the heroine (Reshma, played by Waheeda) in particular is more an echo of Maria in West Side Story, rather than the original Juliet. You will not see Maria or Reshma sit idly by and assume that everything will work out for them, as Juliet does.

Maria and Reshma both act as the writer-appointed conscience of the film: both as the "judge and jury" in the climax, and the example of a new model of absolution rather than revenge. In contrast, Juliet's climax is an act of despair, not a show of personal will or principles or self-sacrifice. If her death DOES accomplish any posthumous social reform, it is not because she meant anything of the kind to happen.

The film is gorgeous in color and scope, experimental in its use of visual symbols, and picturized on sumptuous and stark Rajastani landscapes. I can hardly recall a frame that wasn't worth a hanging in a actual material frame. Observe:

|

| This film may just have more striking desert scenes than Lean's Lawrence of Arabia, and I never thought I'd see that. |

|

| That line of camels in the background was sheer brilliance. |

|

| Before there was Princess Bride, there was this scene. . . |

And, Waheeda in Reshma aur Shera:

The transformation of Waheeda/Reshma from bashful girl . . . hardly able to look her admirer in the eye . . .

To the woman ready to literally defy the gods for the sake of her own beliefs . . .

|

| In BLB's review and comments, a good point was made: Where women are deified, there they are often dehumanized. However, while this film's oddly devotional preface seems to fall into that trap, I think as a whole it clearly shows the reality of female suffering and sacrifice in ways that other famous depictions of Hindi women gloss over. Furthermore, I don't think it prescribes, as much as warns. I'd be surprised if someone watched the film and thought, this is how women *should* act all the time. Instead, I think the film hints and even shouts (through this scene esp.) that even Mother Goddess Durga did not have the power to halt the men's needless violence, and the only solution was for yet another female sacrifice. Essentially, if all the men had acted as they should have, Reshma and many other women would have been able to live the happy existence they deserved. |

One can see that Waheeda knows, intimately, the mind of her character. I almost feel she was pouring out all her inner emotional pain and understanding of the female condition into this role . . . as if she knew that she herself was reaching the limit of the average 10 or 15 years of peak stardom that Bollywood actresses tend to get and wanted to put everything she had into one last great swan song.

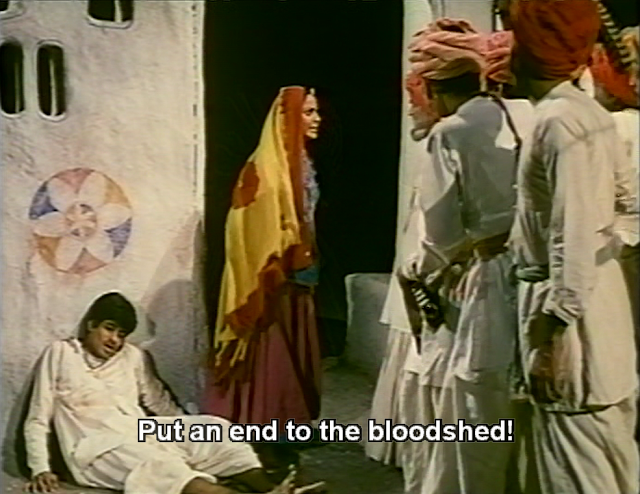

And by the way, it didn't hurt that Rakhee (I have give a shout-out to my house favorite) was also brilliant in her bit role in this film as the new and quickly widowed-bride. Her moment of truth--when given the chance to kill her husband's murderer--is breathtaking.

But was the suffering liberating?

It's all well and good to praise strong performances. But are the female characters strong in any way worth emulating? Would I want my own daughter to look up to Reshma as a role model? Would I advocate for similar action in a similar situation? When all is said and done, does Reshma end on a more liberated note than she started on? Does she wield control over her own choices in a meaningful way? |

| Shera teases Reshma with the usual line: because he is male, and Rajput he is going to steal her away by force. Reshma is not amused. It's too close to the truth. |

*Spoilers ahead.*

"No" is a fair argument, if you focus on some of the less positive female ideals present in the film.

The most problematic ideological theme in this film is that of Sati, or the widow's suicide on her husband's funeral pyre. Reshma's idealization of the Sati is the least liberated facet of her psyche, and leads to her most "debatable" choice (debatable from a standpoint of liberation, at least).

One can choose to look at Reshma's "Act of Sati" in two or three ways.

1. One could see her idealization of suicide in purely historical terms. Intense social pressure and duty once led many women in pre-modern India to throw themselves on their husband's funeral pyres. Though it had been banned by Reshma's time, perhaps it retained currency among her people as an ideal of loyalty. One could argue that the film didn't intend to romanticize such a horrible act in any way, but rather acknowledge it's continued presence in culture as a commonly held ideal of womanhood. The ideal apparently held enough currency to justify the Rajasthani government's issue of the Sati Prevention Act as late as 1987.

2. One could interpret the "is" of the film as an "ought," assuming that because Reshma idealizes sharing the death of her chosen husband (if not her legal husband), that we viewers should idealize it, too.

3. Finally, you could view it as a descendent of several streams of ideals from non-Sati symbolic traditions. Perhaps Reshma was following in the tradition of mad Byronic love, or the Sufi concept of pure love as equivalent to annihilation, or more overtly--the fated death of the lovers in Romeo/Juliet or Tristan/Isolde. Rather than an ideal of duty or loyalty, this is a romantic ideal. Reshma doesn't know how to live without her beloved, and finds it better to die with her beloved than live without him.

My conclusion?

I think different streams of romantic symbolism are united here, certainly. I also think Sati was a controversial and potentially dangerous symbol to choose--and I don't think Sunil Dutt or any of the minds behind the film would disagree. This film was risky, in a lot of ways. It merged a lot of different ethical systems, and tried to come up with an ethic of its own.I gotta respect it for that. If I were to guess, I would say that the intended meaning of the "Sati" as a symbol was to reinvent the wheel. (There ARE a lot of circles and wheels in this film, just ask any commentator.)

I would guess that this film wants us to see personal sacrifice (the sacrifice of love, life, personal feuds, family, and community status) as a BETTER way.

|

| Random aside: You can tell this film was beautifully scripted just from all the foreshadowing in the early dialogue alone. |

I would deem this new ethic a noble one. Better than the alternative, surely. But is was the suffering that got us there *liberating?

I would argue that it is, on three levels: *Spoilers*

1. The self-sacrifice for a higher goal is Reshma's choice. It's overboard and symbolic to the extreme, yes. But it isn't being forced upon her by the community around her. In fact, she's going against community ideals in this circumstance.

2. All this sacrificing is not for Reshma to bear alone. Shera also sacrifices his own principles in an attempt to make up/bring to justice his own family as participants in the murder of Reshma's family. In doing so, he also sacrifices himself, saying that he has ruined himself/their love for "this birth," and that he would have to "wait for the next birth" to be with Reshma.

|

| To be fair, three out of five of Shera's family members were just asking for it. Just look at Vinod Khanna being all sultry in his evilness. |

|

| Shera says to Reshma, "I betrayed my principles, but my principles did not betray you." |

3. Though the men (and women) have been bound to the cycle of blood feuds, the villagers seem ready to let it go after Reshma's and Shera's extreme action, as they all pile their guns on the funeral pyre. Smells like hard won liberation to me.

|

| One always wishes that the next generation will have it better. And sometimes, that wish even comes true. |

In summation?

Waheeda is my new fave. That is all. ;)*Even I'm tired of "liberating." Feel free to suggest another term for switching up purposes. Not "freeing,' tho. Too awkward, not broad enough in scope. And "agency" is over-used, however much I love the term.

so emotionally charged this write up is, that i wish, i can carry on reading this article again and again. i think you have described the women's view so nicely that i will be remaining rleveant for many centuries in India. And no surprise after a century i will be find myself reading it again. Social reform takes time. But in this gender discrimination in our society will thake longer? than needed. Thanx for writing so nciely. I am jealous

ReplyDelete